By Troy Miller

Senior Researcher and Policy Analyst, Florida College Access Network

When the U.S. Department of Education released their College Scorecard two months ago, we remixed it for Florida, showing retention rates, loan defaults and median borrowing amounts on an interactive map. That was the easy part. Understanding what it all means has proved to be much more challenging.

In preparing for a webinar we hosted recently on the College Scorecard and its usefulness to Florida’s college-going students, we took a closer look at the data to learn why graduation rates, loan defaults and median borrowing amounts at the state’s higher ed institutions need to be considered in light of the socioeconomic profiles of students’ families.

Beware how you compare. In President Obama’s 2013 State of the Union address, the President stated that the College Scorecard would help students and families, “compare schools based on a simple criteria – where you can get the most bang for your educational buck.” Comparing colleges to one another the way the Scorecard is currently designed takes some effort and discretion. Metrics like cost, borrowing amount and graduation rates are placed on scale relative to other institutions that primarily grant similar awards in the nation, not the state. Let’s look at the University of North Florida, which has a 6-year graduation rate of 49.5%. Compared to other 4-year institutions in the country their graduation rate appears to be average (51st percentile). Related to other similar institutions in the state, however, UNF’s graduation rate ranks just below the top-third (65th percentile).

If graduation rates were shown relative to similar institutions in Florida, UNF’s would be a bit higher (in red)

If graduation rates were shown relative to similar institutions in Florida, UNF’s would be a bit higher (in red)

This is just one example of how comparing schools and metrics can provide some challenges. Others like the Institute for College Access and Success (TICAS) have pointed out how a college’s median borrowing amount can be misleading because the amount shown reflects all federal loan borrowers who entered repayment, regardless of whether the student graduated or not. This is a very important distinction. Take two similar (primarily bachelor’s degree granting) schools in Florida – Hodges University and the University of Florida. Students leaving these institutions leave borrowing nearly the same amount, roughly $14,000, but only 57% of first-time, full-time degree-seeking students returned at Hodges the following fall, compared to 95% at UF. In fact, the 6-year graduation rate for students at UF is over 6 times higher at UF (83.7%) than what it is at Hodges (12.5%). Those of us who follow higher education know the characteristics of these institutions are far more different than they are similar (selectivity, enrollment, etc.), so looking at the median borrowing amount by itself can be very deceptive. This is where the College Navigator can be of some good use.

A high median borrowing amount is bad, right? This is not as easy of a question to answer as it sounds. If you are a student about to begin their first degree in college, cost is likely a factor and the prospect of piling on debt to get a degree is justifiably a daunting proposition. But the borrowing amount of an institution is a fairly narrow and (again) potentially misleading figure to base a college decision on. Research consistently shows the economic advantage associated with attending college favors those who complete a degree. This is why graduation rates are included in the Scorecard — the potential value of attending college is at best realized after earning a degree.

In Florida, however, high borrowing amounts are not necessarily associated with high graduation rates (view chart here). This means in some cases colleges with higher graduation rates are actually more affordable in terms of median debt. In all cases, the amount of debt a student is likely to attain while pursuing a degree is troublesome relative to one’s ability to pay it off, which is why loan default rates are a very important piece of the college affordability puzzle.

Take heed to high default rates. We hear a lot about how cheap college is in Florida, which by and large is the case. Despite recent increases, public tuition and fees still ranks near the bottom compared to other states. It might come as a surprise then that Florida has the 7th highest borrower default rate in the nation at 16.2%. How could this be? What makes college affordable to a person is not how much it costs – it’s a person’s ability to pay it. A useful analogy for college affordability is the weather. A person arriving in 50-degree Tallahassee from 15-degree Chicago will experience the weather differently than a person arriving from 82-degree Miami. What seems expensive to one family is relative based on their circumstances.

Students default on their federal loans once they enter repayment and fail to make a payment for 270 days (9 months). Repayment is typically required once a borrower leaves college or drops below half-time enrollment following a 6 month grace period. The consequences of defaulting on student loans are severe. Your loan is assigned a collection agency and reported to credit bureaus, damaging your credit rating. Federal and state taxes may be withheld and the debt is not subject to customary bankruptcy laws which means, barring an extreme case, a loan defaulter will carry the debt with them until it is completely repaid.

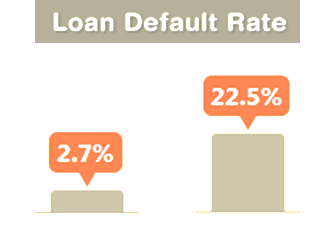

The loan default rates at the University of Miami (left) and Bethune-Cookman University (right) are starkly different — but so are their students

It might be safe logic then to assume that a low institutional loan default rate means a college does a good job of graduating and helping students find gainful employment, since those two elements likely make it possible for a student to make loan payments on time. This is a generalization that again, like the other metrics, requires some caveats. Take two institutions in Florida with very low loan default rates, the University of Miami (2.7%) and the University of Florida (3%). These are two of the most selective institutions in the state, which also happen to enroll a relative small share of students from low-income households. Research shows on average, only one in 10 students attending selective campuses receives a Pell Grant compared to 30-40% at less selective colleges. Our own analysis shows families of students attending the University of Florida report to having average income levels exceeding $103,000 — much higher than the average income level of the other 10 public universities ($66,410).

Providing this context is important, because while we would expect students who attend selective and prestigious institutions to graduate in higher numbers and perform better in the labor market, we also want higher education opportunities to be presented to highly-qualified, students who come from low-income backgrounds. Institutions who enroll high numbers of such students often experience lower performance on higher education accountability metrics (like default rates). This means comparing borrowers from the University of Miami (19% Pell recipients) to borrowers from Bethune-Cookman University (78% Pell recipients) is one that requires some perspective. While high default rates are highly politicized because of their cost to taxpayers, research shows they are not necessarily effective for conveying the quality of institutions.

Some straight-forward points to keep in mind while considering loan default rates in the college decision making process is that high default rates are most prevalent among students who attend for-profit colleges, students from low-income backgrounds, students with dependents and that completing a degree is the single greatest predictor for not defaulting. That means completion definitely matters, so anyone surveying college options should examine closely each institution’s graduation rates, as well as their own commitment and capacity to finish.

Those looking for definitive answers related to college choices might be discouraged by what they read here, but the process as it stands is far from perfect and is a reminder that the discussion prompted by the release of the Scorecard is healthy and warranted. I recently heard a person at a higher education event question how many admission officers on college campuses are currently trained to provide adequate information about the College Scorecard metrics to students and parents themselves — a very honest and prudent observation. Other online resources have taken shape, such as California’s Student Success Scorecard, the Chronicle’s College Reality Check, the Florida Department of Education’s Smart College Choices, as well as our own Florida C.A.N.! College Scorecard. Some institutions like the College of Saint Mary have resorted to releasing their own version of the Scorecard. As more data and resources become available, we need to make responsible comparisons so the students who stand to benefit from them can make more informed college decisions.

~Follow Troy Miller on Twitter @TroyMillerFCAN